Protecting viewsheds on National Historic Trails

Less than 30 miles from the Nebraska-Wyoming border, an etched wagon wheel marks the grave of Rebecca Winters, a Mormon woman who died of cholera in 1852. She and her family were early pioneers in the westward migration that hundreds of thousands undertook in the mid-nineteenth century, seeking gold, land, religious freedom, or a new future on the American Frontier.

Many of these travelers followed similar paths west along broad, flat river valleys. So many moved along the Platte River that historians later named it “The Great Platte River Road.” Four trails through Nebraska and Wyoming overlapped or ran parallel, marking a formative era in the Euro-American development of the American West: the Oregon Trail; the California Trail; the Mormon Pioneer Trail; and the Pony Express, a short-lived mail service.

“This is one of the most iconic landscapes of American history,” said Lee Kreutzer, cultural resources specialist with the National Park Service, “as important as the Liberty Bell. And it should be protected for all generations to appreciate.”

One hundred and fifty years ago, an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 men, women, and children carted their wagons across a landscape very different than the one we see today—wide, lush prairie rolled as far as they could see.

Today, travelers follow nearly the same path on Interstate 80, flying past monoculture corn and soybean fields and the apparatus of industrial agriculture at 75 miles an hour. Today, the original “viewsheds” of these trails are largely gone.

“It’s really difficult in an urban setting to get a feel for what it was like in 1850,” when views from the trail include modern buildings and roads, said Travis Boley, association manager of the Oregon-California Trails Association. In many places, “there’s no viewshed from the area to save anymore,” Boley said. And that’s true for much—but not all—of the trails’ lengths.

Farther west in Nebraska and Wyoming, the rural nature of the landscape has helped preserve some of the historic viewsheds. In such places, those who value the trails’ natural settings are working hard to protect what remains.

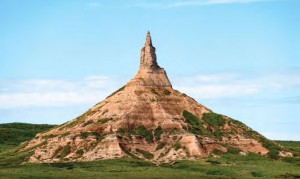

“It’s important to preserve scenery because they’re not making any new scenery,” said Loren Pospisil, supervisor for Chimney Rock National Historic Site. Someone’s sense of history can really be enhanced by the proper context, he added, like historical landmarks. But “once they’re compromised, they stay compromised.”

![]()

Congress designated the four aforementioned routes as National Historic Trails. The trails run through several states, crossing a patchwork of private, federal, and state lands, and as a result, most are jointly managed by several different agencies. Even with collective management agreements, protecting these trails—and their viewsheds—can be challenging.

“It’s difficult, but it’s that way on purpose because Congress didn’t want a 2000-mile linear park with solid boundaries,” Kreutzer said. “It’s a matter of partnerships.”

Protecting sites and sections of historic trails can be especially challenging in a state like Nebraska where nearly all property is in private ownership. Private landowners donated Chimney Rock—whose whittled peak served as a guidepost for westbound emigrants through Nebraska’s broad panhandle—to the Nebraska State Historical Society in 1941. Site Supervisor Pospisil estimates they receive about 25,000 visitors a year, several of whom are retracing their own family’s westward experience through the diaries of their ancestors.

Pospisil said manmade intrusions on the landscape, like family farms, aren’t necessarily the problem, “but power lines, windmills, those are the kind of things that detract” from scenic views. Though a recent attempt to buy more private land adjoining the landmark fell through because of price disagreement, he expects the strong tradition of stewardship by local landowners will continue to protect Chimney Rock’s viewshed in the future.

Thirty miles farther west, the Scotts Bluff National Monument may face more pressures from development, given that it abuts the growing cities of Gering and Scottsbluff. In mid-September, NPS staff and volunteers held a visual assessment workshop for the monument.

“So you’re looking at everything from subdivision developments going in around your national park to high-voltage power lines, wind generating farms, things that would impact a viewshed,” said Resource Management Specialist Bob Manasek.

The workshop is part of a recent shift in the way the National Park Service considers visual resources of lands they manage, modeled after existing methods within the Bureau of Land Management and US Forest Service—agencies that have to balance recreation with energy development, logging, and mining. Visual resource assessments help agencies make decisions on land use by providing a way to evaluate the scenic quality of a place—the integrity of landscape, dominant shapes and colors, how pristine or developed it is—as well as how it’s experienced by a visitor.

Involving volunteers in that process is important, Manasek said, because working with the local community can help guide land planning decisions outside of national parks. Stewards of national historic trails say viewshed protection often comes down to engaging locally with landowners, land managers, and the general public to collaborate on what makes sense.

![]()

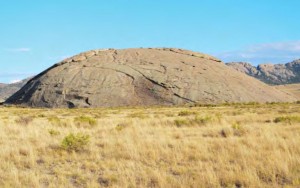

In parts of Wyoming, much of the trails’ historic viewsheds have been changed by development, oil and gas, and increasingly, renewable energy and transmission lines—what Kreutzer described as the biggest landscape change she’s seen in the last decade.

“A lot of us do see a need to protect these viewsheds and these trails, but it’s a competition between that need and the need for power, moving energy to where it needs to go, our needs for minerals and all of these other uses of public lands,” Kreutzer said.

South of Rawlins, the Bureau of Land Management has nearly finished its environmental review of the Power Company of Wyoming’s 3,000-megawatt wind project. When fully built, it will be the largest wind farm in the country, with as many as 1,000 turbines stretching more than three hundred feet high, likely visible from parts of the Overland and Continental Divide National Scenic trails.

But Wyoming also has some of the best trail remnants, particularly in the BLM’s Lander Field Office northwest of Rawlins, where 90 percent of the trail segments retain their original setting. That’s according to Kristin Yannone, a planner who’s in charge of the office’s most recent resource management plan, which specifically outlines protections for the national historic trails.

The BLM Lander Field Office receives tens of thousands of visitors annually. Many are pioneer reenactors and groups affiliated with the Mormon Church. In the past, national historic trails were granted protection in the form of a quarter-mile buffer zone. While the Lander Field Office was drafting their new resource management plan, the BLM released updated guidelines for assessing visual resources.

“We have taken a much broader understanding of what is important to protect for trails,” Yannone said, not only the physical paths but also their viewshed. “If you’re a pioneer or visitor, what do you see? That’s what we want to preserve.”

Instead of the standard buffer, the agency used GIS to project what a visitor could see from the trails, ranging anywhere from three to thirty miles. Inside that new trail corridor, the Lander Field Office prohibited many activities, including surface occupancy for oil and gas, wind development, sand and gravel excavation, and mining. The new plan protects around 450,000 acres.

Yannone points out that her field office is an exception, however.

“We have very few resource conflicts here…we don’t have a lot of oil and gas, don’t have a big expanding population. We haven’t had the challenges—not all parts of country can do that,” Yannone said.

![]()

On a bluff near Guernsey, Wyo., a series of ruts carved by hundreds of wagons persists in the soft rock.

“It’s one of a number of places where you can really stand on the trail and let your imagination flow,” said Lyle Mumford, who leads tours along national historic trails for the Mormon Heritage Association.

Like many modern tourists, Mumford’s group follows the highways that shadow or mirror the actual trails, “so that we can get a feel for the landscape and the landmarks that pioneers were navigating by and learning from,” he said. Last summer, one of Mumford’s tour groups included a descendent of Rebecca Winters. When they visited her grave, “it was extremely moving for him to be there at that spot,” Mumford said.

Therein lies the value of protecting what remains, said Kreutzer, because there’s so little of the original trail left “where you can stand in their wheel ruts and see what they saw.”

By Ariana Brocious

Ariana Brocious is a writer and reporter based in Lincoln, Nebraska. Her last piece for Western Confluence was “One Irrigator’s Waste is Another’s Supply” in the winter 2015 issue.

Interesting story. The story loses some credibility when it makes a vague references to future projects like the Power Company of Wyoming one south of Rawlins. This project is 8 years old and has done more than any project in America to minimize impact on view sheds and wildlife. Yet it is not finally permitted! No major roadways are near this site. The CDT is near here but that is foot traffic.

Reality is that this Wind Factory will become a major draw for people to see clean energy at created by giant indmills. . The issue will be how to showcase the project with minimal impact.

John D Farr

Wyoming